Lee Jacobs Remembers the Santa Cruz Garden

I was a stray dog who had just found a home. The first job I volunteered for in the garden seemed really exciting. The county fair was ending over in Watsonville, and we were told that we could have all the manure if we came to pick it up. Alan wanted it for composting—letting it heat up and cure—to put on the garden as a soil amendment.

Someone lent us a pick-up truck, and Fernando and I were happy to ride in the back. It was a great way to see the new countryside. On our return, Alan gushed about how valuable this manure was for the garden …literally gold. He made us believe and understand that this organic matter was how to build soil productivity. Gesturing toward the steep, baked hillside that he had chosen for its sun-exposure, he said, "The compacted clay-mineral soil lacks organic matter, which is the spark that ignites the abundant flow of life." This is how he developed our love for the garden. I was so proud over a load of manure.

The Garden provided us with food, but each apprentice had to find his own place to sleep. The first week we were sleeping outside near the garden, getting up early before the Mexican grounds-keeper came. "What's the name of the hedge,” Alan asked, testing me as he pointed to where we had been sleeping. He smiled, cupping his fingers to his nose and sniffing. He wanted me to do the same. It was sweet and musky. "Jasmine," he said.

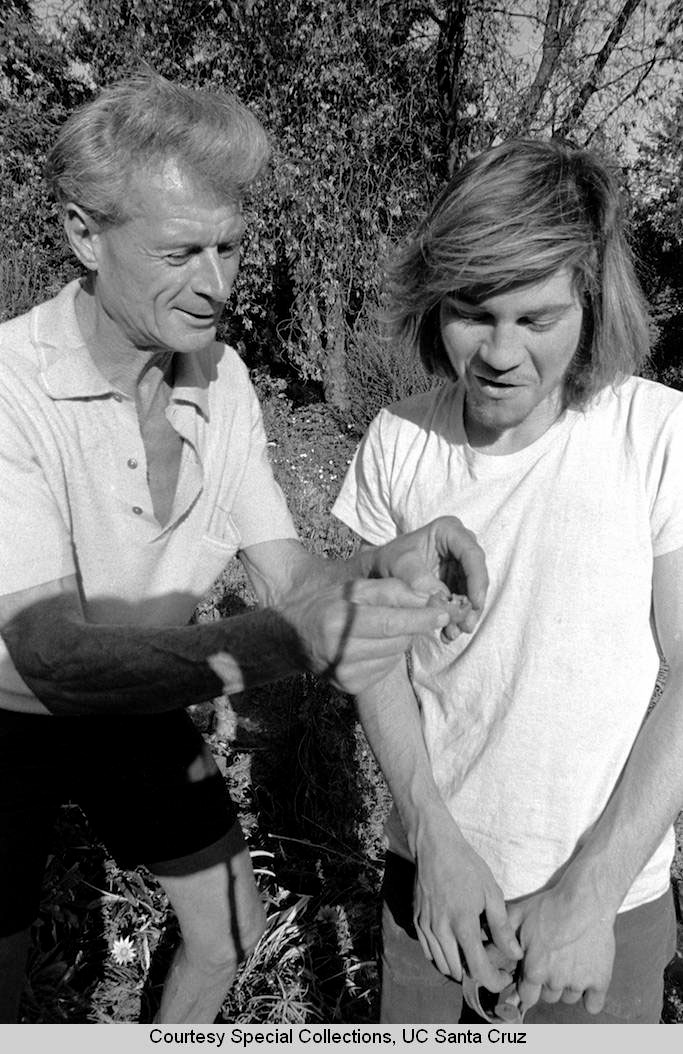

Alan Chadwick and Lee Jacobs in the garden at Santa Cruz

There was quite a bit of undeveloped land on the campus at that time; it has more than doubled in size since then. Walking around in the Redwood forest, I found a ring of Redwoods growing in an almost impenetrable circle, with only two small gaps where you could slip inside. The floor was spongy with roots and 50-60 years worth of needle accumulation. Lying on my back, I looked up 90 feet to the lowest branches of the canopy. It was immensely quiet, protected on all sides, and remote from any foot trails. I learned that these rings form when a mother redwood tree dies; the root system sends up shoots all around the trunk. It was within this organic room that we slept, night after night, for a whole year. Fernando learned to stay quiet so that, even if another dog passed by, we remained undiscovered.

I was totally dedicated to the garden and to Alan, who really was "The Garden." That's why he was so protective of it. In the greenhouse, Alan showed his passion as he raised our awareness of the process of sowing seeds. Holding up a packet of seeds he said, "You are about to commit an act that will begin new lives. Therefore you have responsibility to plan for the success and maintenance of these plants throughout their lives. By planting seeds you are taking part in a sacred ritual. Sowing seed begins a process of releasing the infinite power of life. Each seed is as important as a star in the sky. You are responsible to see that it has the best chance at life." As I see it, Alan protected the garden like a fierce parent in a hostile world.

I did any and all jobs that came up. I loved to dig new beds. It meant you had to dig down one shovel’s depth across the width of the bed and throw that soil back over the bed. Next you use a spading-fork to loosen the soil in the pit that you had just dug. The next row of soil goes into that pit, and so on. After that you get four wheelbarrows-full of compost, spread it evenly, and work it into the first four inches of the topsoil. It made a raised bed with good drainage and an excellent medium for the transplants from the nursery.

I knew that I had been accepted as an apprentice when one day I was scheduled to make lunch. It was our big meal. There were a dozen people working in the garden that day, including apprentices, volunteers, and Alan. I baked two trays of lasagna, using layers of Swiss chard leaves in place of pasta, with garden canned tomato sauce. It was well received, but everyone said that I hadn’t made enough. Alan turned the complaint into a compliment saying. "Nonsense, there is never enough delicious food to go around. The amount was just right."

Never once did Fernando or I beg for his admittance to the garden—dogs were simply not allowed. Luckily Fernando learned his role quickly and didn't follow me into the garden while I worked. He waited obediently near the gate, sleeping and greeting people. Alan got used to being greeted by him. He would talk to the “good black dog" every day. He eventually made Fernando the official Garden Dog. He was to be the only dog allowed to enter the garden. He seemed to know what an honor it was and he attended to his duties with distinction. He didn't wander about the garden but remained at the gate near the chalet as a greeter to all who came.

In my free time I found a Spanish class that I could sit-in on. The instructor was very dynamic, teaching with songs and other cultural elements. I met Juana there. She had come from Chile on a Fulbright scholarship and she was the instructor teaching the class. When she became my girlfriend, my interest in Spanish developed wings. There was so much Spanish to learn. Fernando and I stayed with her in the converted chicken coop where she lived. We had many great meals made with produce from the Garden.

As I said, Alan was incredibly proud and protective of the garden, almost as if it were his own body. He had good reason to be in fear for its future. First of all, he was not a scientist—quite the opposite—he was a temperamental artist. Secondly, the garden was located within the University of California system, operating with government funding and promoting industrial agriculture. California has the largest agricultural economy of any state. Although the Garden Project was tiny—infinitesimal by comparison—big Ag could not tolerate a contrary point of view in their system. Alan had no fear of the power of the industrial and economic forces he was working under in the UC system. As the garden’s success was recognized, his days were numbered.

His most powerful enemy was the Dean of Crown College, Kenneth Thimann, an English plant physiologist who worked on the chemistry of plant hormones. He had worked in Britain during World War II on chemical defoliants to be used on the enemy’s crops—to starve them. It was never used during that war. He is credited as one of the discoverers of the hormone 2-4-D that was used as a defoliant in Vietnam—commonly called Agent Orange. It has been shown to cause birth defects, cancer and a few nervous disorders. After the war, he led the Botany Department at Harvard University. He was well respected in the science community there and only left his position at Harvard to come to Santa Cruz, where he became the main science recruiter at the new campus.

Alan called his work, "Incandescent drivel.” He said, “To take one aspect of a plant, which is harmless in its natural state, and to multiply it thousands of times, is to make a Frankenstein’s Monster to attack the natural world. It is despicable."