Donald Nicholl on the Beginning of the Chadwick Garden

The Roots of Knowledge

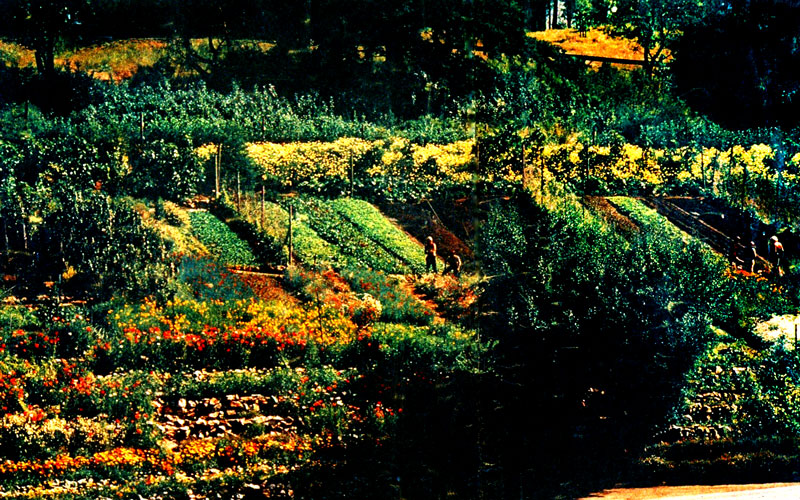

How very strange are the interconnections of human beings, and how unpredictable are the influences they exert on events and on one another. I reflect on this each morning as I go past the Garden, a south-facing slope in the university grounds bursting with blossoms and flowers of every variety which the students by their labours have converted into the most famous four acres in California. And I reflect that all of this issues from the word of David Jones.

It happened in the following way.

In 1966 I gave a talk here about the "sense of place" in David's work. In those days, acutely aware of what devastation the tributes of the Pax Americana were wreaking in Vietnam, the students were alive to the implications of the Roman tribune's words:

"It's the world-bounds we're detailed to beat, to discipline the world floor to a common level till everything presuming difference and all the sweet remembered demarcations wither to the touch of us and know the fact of empire."

And afterwards they came to me and asked how they might acquire a sense of place. I suggested to them that they should start a garden, because in tending roots one acquires roots. By a happy chance (synchronicity?) there was visiting the university Freya von Moltke, the widow of that Graf von Moltke who was executed by Hitler for being a true Christian. She said that she knew the very man to start such a project, a much-wandered Englishman named Alan Chadwick, a gardener of pure genius.

And that is what Chadwick turned out to be. Working on what he calls "French intensive," or "biodynamic" principles, he released a current of life that has flowed through California. As the gardening editor of Sunset has said, because of Chadwick, "Greater things have happened for the gardening public of California than anything that the entire College of Agriculture had come up with in 20 years."

. . . And as I watch the struggle going on over David's Garden I see it crystal clear as symbolizing the struggle that is going on all over the USA, all over the world perhaps, and especially in the universities, for the soul of man. It is a struggle between the technicians of knowing, who "manipulate the dead limbs of our culture as though it yet had life," and the men of wisdom who know how to plant the seeds of life.

Who are these men of wisdom? Isaac Heschel, for instance, and Thomas Merton, who were wise because above all they sought wisdom, which they knew to be "beyond price"; and hence they themselves could not be bought. Whereas you can always hire the technicians of knowing so long as you name the right price—President Kennedy and his successors had simply to whistle down the corridors of Academe for "the brightest and the best" amongst the technicians of knowledge, the brightest and best lawyers and sociologists and historians to come and justify the devastation of Vietnam, the Bay of Pigs, the destruction of Allende, Watergate. All of which was foreseen by Merton and Heschel because they had the root of the matter in them.

But, who, in any of the universities of the world, thinks it their task to nurture men of wisdom rather than technicians of knowledge, even though they see the devastation produced by the latter? For a time here at Santa Cruz there were some, indirectly inspired, perhaps, by what the Garden symbolised. The Garden, to quote Chuang Tzu, "shows The absolute necessity of what has 'no use'."

So in whatever space beyond time David may be I hope he keeps watch over his Garden and recites his own litany: "Mother of Flowers save them then where no flower blows."

Excerpts from an article originally published in: The Tablet: The International Catholic News Weekly http://tablet.archive.netcopy.co.uk/article/12th-april-1975/2/in-the-margin-donald-nicholl

Photo shows the Alan Chadwick Garden at the University of California at Santa Cruz in 1968.