What Makes the Crops Rejoice

What Makes the Crops Rejoice: An Introduction to Gardening

By Robert Howard with Eric Skjei

Little, Brown; 1986

The book title is taken from the first lines of Virgil’s Georgics, a poetic compendium of agricultural lore written in 36 BC.

What makes the crops rejoice, beneath what star

To plough, and when to wed the vines to elms,

The care of cattle, how to rear a flock,

How much experience thrifty bees require,

Of these, Maecenas, I begin to sing.Virgil, Georgics, Book I, 1–5

Bob Howard first found his way into Chadwick’s garden at Santa Cruz in the summer of 1971. Quiet and unassuming, he went about his work in a careful and methodical way. When we unexpectedly met him again, some twenty-five years later, we were astonished to learn that he had written a book about gardening that included an extensive biography of Alan. What is particularly of note is that, in every case where he was able to obtain information about Alan Chadwick from outside sources, this information corroborated the accounts given by Alan himself over the years. This fact lends credence to the other stories that Alan occasionally told about his life.

Research on this book led him to contact Alan’s brother in England, from whom he received information about Alan’s early life. He also was able to track down a former roommate of Alan’s at the theatrical academy of Madam Elsie Fogerty in London. This gentleman remembered Alan well, relating a number of amusing stories that Bob Howard includes in his biography. He also communicated with the Countess Freya von Moltke, who described her friendship with Alan in South Africa, and again, later, when she was instrumental in bringing him to Santa Cruz in 1967.

The introductory chapter of What Makes the Crops Rejoice describes Bob Howard’s initial impressions of Alan, and provides an accurate account of a typical day in the Santa Cruz garden. His daily confrontation with an overly-protective rooster was one that many of us faced in those early mornings. Flower cutting, vegetable harvesting, morning watering, compost collection, and many other tasks are faithfully described, and these do capture the flavor of the life of those times.

The rest of the book treats gardening in more general terms, but always with reference to the techniques employed by Alan Chadwick. Various chapters treat other famous gardeners, bringing a personal flavor to this broad introduction to backyard gardening. Howard also describes his own foray into the world of homesteading: For three years or so, he farmed 40 acres in the mountains of Missouri, and emerged much the wiser for the experience. He includes chapters on planning the garden, obtaining plants and seeds, cultivation, compost making, fertilizers, and other topics which would be helpful for a first-time attempt at raising vegetables for the novice. He concludes with a narrated tour of an idealized farm from his own imagination, describing the many interrelationships that exist between the plants, animals, and human beings in such an integrated and diverse project.

The biographical chapter of Alan Chadwick is the most extensive and well-researched that has been done to date. It has been the primary source for the majority of the other accounts of Alan’s life written since 1986 when Bob Howard first published this book. It is an outstanding contribution to our knowledge of the life of this remarkable man.

* * *

[ed. note: In May of 2015, Robert Howard granted us permission to reprint the chapter from What Makes the Crops Rejoice that recounts Alan Chadwick's biography. With gratitude for his generosity, we reproduce that chapter below.]

Chapter Eight: This Too Could Be Yours

Alan Chadwick was born on July 27, 1909, in the fashionable seaside resort of St. Leonard’s-on-the-Sea in southern England. The society that Chadwick grew up in was a paradoxical mixture of two worlds: village and empire. On the one hand, it was still very much the timeless, rural England of Miss Jekyll’s artisans and their cottage gardens. On the other, it was also the world of colonial imperialism, a world in which the sun never set on the Union Jack.

Alan’s aristocratic family lived on a country estate with one foot in both these worlds. Alan discovered gardening as a boy, first simply by watching the working gardeners his father employed, and second by visiting the great gardens of Britain and Europe.

Although Alan’s father, Harry Chadwick, had trained as a barrister at Oxford, he never practiced the law. Instead, he sold two inherited estates, Pudleston Court in Hereford and Yarna Wood in Devon, shortly before Alan’s birth and devoted himself to sports, particularly horse racing and rowing. In fact, it was at the rowing competitions held at Henley-on-Thames that Harry Chadwick first met his future wife, Elizabeth Alcock, who would become Alan’s mother. The marriage, in 1907, was the second for both Harry and Elizabeth, and so Alan was born into a family of older half brothers and sisters, as well as one elder full brother, Seddon.

Before meeting Harry, Elizabeth had been the proprietress of an elegant Italian restaurant in London’s West End, known for its lively bohemian atmosphere and frequented by actors, actresses, and members of society. Elizabeth was an accomplished painter and pianist and was also active in the Theosophical Society, where she made the acquaintance of, among others, Lady Emily Lutyens, Edwin’s wife. Alan was, in Seddon’s words, “a great favorite of his mother,” and she clearly represented for him the artistic and spiritual side of life. Both parents were bilingual, Elizabeth in German and Harry in French.

Until he was about nine years old, Alan’s family lived at Fawley, a ten-acre country estate in Sussex, near Eastbourne. Located in Hampden Park, Fawley must have been the picture of turn-of-the-century English manor life. The three-story brick and tile house, with billiard room, large main hall, and drawing room, was manned by a staff of five: a butler, a cook, two maids, and one other “inside” person. The large grounds, maintained by two gardeners who lived in a separate cottage, included a fair-sized kitchen garden, greenhouses, and a small lake with a boat. (A good idea of what life on such an estate was like can be obtained from reading Elizabeth Yandell’s Henry, included in the Reading Guide at the end of this book.) The Chadwicks moved in influential circles: Harry went shooting with his neighbor, Lord Willingdon, who was to become Viceroy to India in 1931. A great uncle, Richard Seddon, was liberal Prime Minister of New Zealand in the early years of this century.

Due largely to his mother’s influence, Alan was raised as a vegetarian and a pacifist, in an environment alive with occult speculation. When a schism developed in the Theosophical Society, Elizabeth Chadwick followed those who adhered to the teachings of Rudolf Steiner, founder of the new Anthroposophical Movement. Steiner, a magnetic personality himself, developed a spiritual philosophy based in part on his study of Goethe. He lectured widely on topics ranging from education to architecture to medicine, as well as farming. The latter lectures, given to a group of farmers at the Koberwitz estate near Basel, Switzerland, in 1924, form the basis of the biodynamic approach to gardening and farming, which is still thriving today. Alan first met the philosopher during Steiner’s speaking tours in London in the early 1920’s and was deeply impressed by the man.

Alan and Seddon attended a number of preparatory schools, in both England and Switzerland. Since their parents were fond of traveling on the Continent, the boys’ education was a bit erratic, but this had its compensations: both became trilingual, in French, German, and English.

From an early age, Alan was interested in flower painting, and his art instructor at Fox and Russell’s Academy in Vevey, Switzerland, tutored him in watercolor and in painting flower miniatures. One of Alan’s favorite flower portraitists was the French artist Ignace M. J. T. Fantin-LaTour.

During these same peripatetic years, Alan also visited many private and public gardens in England and France. These experiences made so strong an impression on him that, while most of his peers were deciding whether to go to Cambridge or Oxford, he was planning to train in horticulture. In 1925, when he was only sixteen, he entered an apprenticeship at the Hughes Glasshouse Nurseries in Dorset, under Emil Hartmann, a skilled market gardener who was then in his midsixties. The Hughes firm specialized in tomatoes, lettuce, and other salad crops, as well as chrysanthemums and carnations of the old, intensely fragrant Malmaison type. Alan concentrated on learning the commercial methods of producing these flowers.

A year later, having heard about the French gardener Louis Lorette, Alan accompanied his parents to Paris and stayed on to study at the Lorette nurseries in St. Cloud. Lorette had developed a complicated but effective technique of summer pruning through which he was able to induce fruit trees to bear abnormally high yields, the fruit being so plentiful as to almost hide the leaves, particularly in pear trees. While in France, Alan also visited the vegetable and fruit gardens at Versailles, a place that represents a high point in the history of intensive production, under the direction of Jean de la Quintinie, gardener to Louis XIV.

By 1927, Alan had returned to the southern coast of England to pursue a second apprenticeship at another Dorset market garden, Haskins Flower Nurseries and Glasshouses. In the 1920’s, the characteristic feature of an intensive market garden was its abundance of glass. In order to compete against the produce brought in by rail from more distant, less expensive acreage, intensive gardeners located close to urban centers turned more and more to the use of cold frames and cloches (explained further in chapter 11 to raise the out-of-season specialty crops that fetched higher prices at the market.

Throughout his life, Alan was impetuous, and in the following year his career took a sudden but hardly inappropriate turn. As Alan himself told it, in an interview called “Garden Song”* filmed near the end of his life, he went to see a play one day and was so captivated by the medium that he decided on the spot to become an actor. And he did in fact proceed to train, both for the opera, as a bass baritone at the Carl Rosa Opera Company, and for the theater—he took lessons from one of the leading figures in twentieth-century English drama, Elsie Fogerty.

[*Available from Bullfrog Films, Oley, PA 19547]

Miss Fogerty’s Central School for Speech Training and Dramatic Art was the embryo of England’s National Theatre, as well as the training ground for many great actors, including Olivier, Gielgud, Peggy Ashcroft, and Ann Todd. Students at the Central School during the years that Alan is likely to have attended staged plays by Bernard Shaw and performed as the chorus in T. S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral, among other productions.

Miss Fogerty was, by all accounts, much like Alan and may well have served as a model for him in many respects. She too was eccentric in manner and dress, passionate in her love of the dramatic moment, and she could be shockingly direct. Above all, she transmitted to her students a deep love of her craft.

Throughout the 1930’s, repertory theater was Alan’s life. He appeared in contemporary plays like Rebecca, Petrified Forest, and Abraham Lincoln, often in the lead role, and toured rural Ireland with the Shakespearean Company of one of the last and best known of the great English actor-managers, Anew McMaster.

Shakespeare became a touchstone for Alan for the rest of his life. In his garden talks in Santa Cruz, he often recited soliloquies from the plays. Friar Lawrence’s speech in Romeo and Juliet—“O, mickle [great] is the powerful grace that lies/In plants, herbs, stones, and their true qualities”—was a favorite, for obvious reasons. Alan was perceived as something of a character at Santa Cruz, and it only added to his reputation when he, a gardener and dirtbuilder, gave Shakespearean readings on the campus and appeared in a play as, no less, a madman.

As World War I had changed Miss Jekyll’s life, so World War II disrupted Alan’s. At first, because of his pacifist upbringing, he stayed out of military service as a conscientious objector and continued with his theater career. A fellow actor, Richard O’Donoghue, now Registrar at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, performed with Alan in the Hull repertory company in 1940, with German bombs falling nightly all around them. According to O’Donoghue, Alan was at that time sensitive and yet full of humor, inclined to such mischief as telling risqué jokes under his breath while on stage, to provoke his younger colleague to laughter in midsentence. Alan kept a dartboard in the dressing room that he and O’Donoghue shared, and the two were used to playing a game during the intermission.

O’Donoghue remembers Alan as a striking figure—tall, with a shock of thick black hair and a piercing gaze. Rustling a billfold full of five-pound notes, obtained from a stockbroker friend, Alan was fond of entertaining Richard and other friends with occasional repasts at a local hotel, a welcome break from the fare provided by their meager actor’s pay. After a play, Alan often headed back to the flat that he shared with O’Donoghue and an actress, to pass the night listening to classical music, playing whist, and smoking cigars.

As the war grew worse, Alan’s pacifist scruples gave way to his patriotism, and he joined the Royal Navy as a cadet trainee on a minesweeper. He was then just over thirty years old. Posted to India, he was stationed in Bombay and soon worked his way up to the command of a corvette (similar to the U.S. Navy’s PT boat). There his legendary temper once got him in trouble. Upset over something, he threw a copy of the Koran across the deck, causing his Indian crew, Muslims all, to promptly go on strike. Only a public apology enabled Alan to regain his command.

When the war ended, Alan returned to England and repertory work on the south coast for a couple of years before deciding, in about 1950, to join the National Theater Organization starting up in South Africa. Although he had no use for apartheid and little enthusiasm for constant touring, the open air, dramatic landscape, and the rich flora of South Africa appealed to him greatly. As his good friend Freya von Moltke told me, “He disliked so much living in sordid or little hotels on his tours that he often put up a tent somewhere in the open and spent the night there. And the open is just round the corner in all these small towns, where they used to play.”

And then along came a chance to garden again. In 1952 or so, he took the job of head gardener at the Admiralty House in Simon’s Town, then the residence of Vice Admiral Peveril William-Powlett. In the age of sea power, the Cape peninsula was one of the most important strategic positions in the world and Simon’s Town was the headquarters of the British South Atlantic Command.

The formal gardens at Admiralty House were, when Alan took them over, more than 150 years old. Meticulously kept, they were used for official receptions and entertaining guests of state. Like Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, the land they are built on was originally sand dunes: their very existence is a testament to the skill of the original gardeners. Today, large milkwood trees to the east of the big, white, Dutch-style main house are striking vestiges of the indigenous coastal vegetation. The gardens are a remarkable mixture of native and imported garden plants: Plumbago auriculata and bird-of-paradise flowers, endemic to South Africa, flourish alongside hydrangeas, bedding roses, and bougainvillea. (The bird -of-paradise plant, Strelitzia reginea, was named in honor of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitzia, Queen to England’s George III when, in 1814, Admiralty House first became the official residence of His Majesty’s naval commander-in-chief there.)

In the late 1950’s, in anticipation of South African independence, which took place in 1961, England vacated Admiralty House. A British presence was maintained in the area, though, and the Vice Admiral then in charge, Sir Geoffrey Robson, took Alan along with him when he moved to the new official residence, up the coast on Wynberg Hill, in 1957. Here, to the best of my knowledge, is where Alan first created a major garden.

Admiralty House gardens

From the house at the crest of Wynberg Hill, the land slopes gently downward to False Bay below. Across the face of the hillside Alan dug deep, wide beds, establishing a series of terraces whose effect is both formal and lush. Freya von Moltke visited him there and recalls that “Alan’s cottage…was perched on a rock about 100 metres above the sea. The shore is mostly flat, white sand and strong waves, but opposite… at the other side, east, are big rocky mountains. The sun must rise above them.... Alan said that animals visited him in that cottage at night without any timidity. He could have left his windows and doors open at night during the warm season, which is long in South Africa.” Alan did have an affinity with wild animals and was good at imitating bird calls—I can remember him quacking just like a duck.

But South Africa couldn’t hold him, eventually, and after nearly a decade of acting and gardening there, he left, sailing for the Bahamas in 1959 to work in the gardens of a private estate. From there he was hired to take up a similar position in Long Island, and thus in the early 1960’s came to the United States for the first time.

Alan soon found, however, that New York winters were hard on his back, which had been injured twice, once during the war and then again in South Africa, while he was playing a game that is something like our leapfrog. By 1965, he was longing for a change, for a warm place where he could again live close to nature. After getting in touch with his brother Seddon for the first time in many years, Alan decided to try Australia and New Zealand. Seddon was to arrange introductions to friends and relatives there.

Before he left, Alan again contacted Freya, who was then living in Vermont. After warning him that he might not like Australia, she told him she was herself planning to be in California in the fall of 1966. Her friend the philosopher Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy was to be lecturing at a new campus of the University of California, in Santa Cruz. Situated on over 100 acres of former ranchland in the hills overlooking Monterey Bay, the campus, Freya had heard, was an oasis of grassland meadows, wildflowers, and groves of coast redwoods. Tempered by the nearby ocean and low-lying fogs, the climate was mild, Mediterranean. Prophetically, Freya commented that Alan might like working there.

About one year later, in the spring of 1967, Freya was indeed in Santa Cruz, having lunch with philosophy professor Paul Lee. An effort to start a garden on the campus was afoot, one that had attracted many supporters. Students, faculty, and staff alike shared a common appreciation for the superb natural beauty of the site. The first chancellor at Santa Cruz, Dean E. McHenry, a former farm boy from Lompoc, California, had instituted a rule prohibiting any tree larger than ten inches in diameter to be felled without his approval. As a result, roads and footpaths on the campus wind around trees, and the single road leading to and from McHenry Library is only one lane wide.

Another catalyzing force was a talk on the Welsh poet David Jones, given by visiting professor Donald Nichol. Nichol suggested that the campus could give form to its affection for the genius of its place in three ways: a bell within whose sound they would live, a statue, and a garden. All that was needed, mused Professor Lee to Freya, was someone to man the spade.

As it happened, Freya had just received a note from Alan. As she had anticipated, he had not found Australia to his liking, and he was on the move again, heading for San Francisco, where he hoped to visit her. At Lee’s comment, she replied, “The new gardener is arriving on the first of March.”

And so it was that on the appointed day, Freya met Alan at the Embarcadero in San Francisco and drove him back down the peninsula to Santa Cruz, with his sea chest full of naval uniforms, old boxes of theatrical makeup and memorabilia, and a few of the pieces of Pudleston silver and china that his mother had left him.

They met Paul Lee on the campus near Cowell Fountain. Alan was a bit formal, hesitant even. As Paul Lee remembers it, though, the big hand that enveloped his reassured him that Alan could do the job. After a walking survey of the campus, Alan announced that he had found the right spot for the garden, on a hillside just above Cowell College.

He undoubtedly had many reasons for choosing this location. His proclivity for hillside gardening is one. Another is that it placed the garden at the entrance to the campus, forming a natural symbolic passage to the world of learning. And most important, the view from that spot out across Monterey Bay is very much like the view eastward from the Admiralty House gardens in South Africa across False Bay. Fundamentally, it is a romantic view, one that unites memory and vision.

The very next day, Alan went into the nearby town of Santa Cruz, bought a spade and a wheelbarrow, and with as much élan as he had used in taking up acting, started to dig. For the next two years, without taking a day off, this fifty-eight-year-old man worked from dawn to dusk every day of the week. Those who were there say he worked more heroically than they had ever seen anyone work before. Students who wandered into the garden often stayed to help, even though they were driven tyrannically; the brilliance and intensity of Alan brought them back day after day.

Freya was one of the reasons Alan worked as hard as he did. Her voice was one of the most respected in his life, and she had charged him, upon his arrival in California, with a mission: he was to help offset the dehumanizing forces of the technological age by sharing his love and knowledge of nature with others. Santa Cruz in the 1960’s, a haven of countercultural enthusiasm for the natural and the humanistic, was probably one of the most favorable places in the country to initiate such an undertaking.

By the summer of 1969, two years later, the four acres of garden on that hillside had blossomed into rich fertility. From thin soil and poison oak had sprung an almost magical garden that ranged from hollyhocks and artemisias to exquisite vegetables and nectarines. Old-fashioned roses—the rugosas Agnes and Cornelia, the old cabbage rose la Reine Victoria, Columbia, climbing Will Scarlett, Alchemist, Sombreuil, Shot Silk, Crimson Glory, and Madame Alfred Carrière—twined up the railings of a small chalet there. Every week a special basket of produce and flowers was taken to Chancellor McHenry’s house. Flowers festooned the offices of the university staff. A covered garden stand across the road from the garden offered food and flowers free for the taking.

Alan soon had dozens of apprentices. Though he had never taught before, he threw himself into cultivating young minds and their gardening skills. His manner of teaching was the simple, classical one of combining practicality and vision. He would first demonstrate how to do something, and then put the student to work doing the same thing. And like the novice monks at Wilfred’s Reichenau, students often found that this way of cultivating the earth led to cultivation of their own perceptions.

As always, Alan was nothing if not mercurial. One of his early apprentices, Michael Zander, remembers planting dahlias with him. After digging an especially large hole, and layering in leaf mold, bone meal, and aged manure as carefully as if they were making a fine French pastry, they would set and water the plant. But by the next time they planted dahlias, the recipe would have changed.

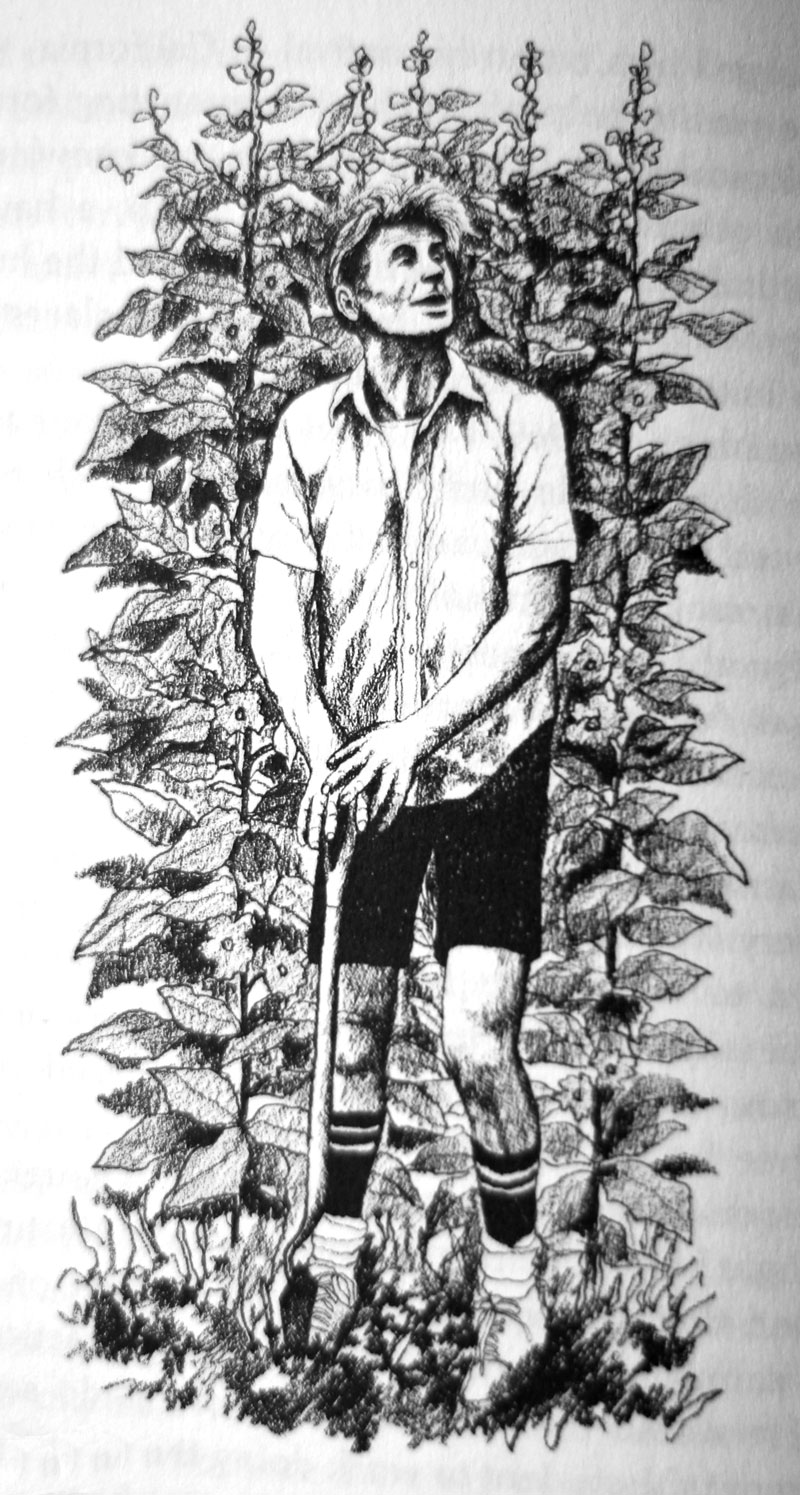

Alan Chadwick

As well as demonstrating garden practice, Alan sought to communicate vision. Michael and another early student of Alan’s, Steve Kaffka, often visited Alan’s apartment on Sunday mornings. There they would listen to opera, drink freshly ground coffee (sweetened with Eagle condensed milk), and munch on Alan’s blackberry tarts. Alan would talk about gardening and perhaps enact something like the turning of the seasons, beginning with winter.

Hunched over, cupping his hands about his face, he would exhale a long, rasping, shallow breath, instantly creating a vivid image of contraction, sleep, dormant potential. Then, opening his arms into spring, his back would straighten up, his voice begin to sing, a smile play across his face. As he reached summer, his voice would become full, expansive, resonant. His outstretched arms evoked the open sky, his eyes seemed to reflect the full sun. Then, at the word fall, his back would bow again, his shoulders bending inward. His eyes would cloud over, his hands and arms curl in across his chest. Drawing in his breath, he would turn his face down and away, as if to shield it from the approaching chill.

Even in play, Alan exhibited the same forceful passion he brought to his garden labors. One of his recreations as a young man had been boxing, and in his cruise chest were a couple of pairs of old trunks. One day he and Professor Lee, a big man, easily outweighing Alan, squared off in a friendly match. Rather than adopting a predictable defensive strategy, avoiding Lee’s advantage and hoping to tire him out, Alan’s approach was to overwhelm his larger opponent in a matter of seconds with a wild, windmilling, all-out style of attack.

Page Smith, another key supporter of the Santa Cruz garden and at that time Provost of Cowell Collage, was similarly surprised in a tennis match with Alan. Somewhat taken aback by Alan’s unorthodox but highly effective style of play, Smith took his time picking up the balls, which provoked a caustic shout from his partner: “Did you come here to play tennis or what?” Smith stepped up the pace a bit, but it wasn’t enough for his passionately competitive opponent. After the next point, Alan jumped over the net and ran around on Smith’s side of the court, retrieving the balls himself in a quirky display of one-upmanship.

At the age of sixty, Alan was in exuberant good health. He continued to ride a bicycle, for the sheer joy of it, and generally avoided using automobiles, considering them a threat to humanity. He did, however, own a car, an old blue-gray Rambler that a student had given him. It had the words This too could be yours painted on one side.

One day Alan needed to take the car into town. Driving away from the campus, on a downhill road, he evidently picked up too much speed and was pulled over to the side by a policeman. Alan got out, nodded at the legend on the side of the car, and tossed the keys into the startled officer’s hand. Nonplussed by this casual approach, the man over-reacted and made the mistake of drawing his revolver. Alan reacted instinctively: a left jab, a quick move, and the gun was first in Alan’s hands and then in the weeds by the side of the road.

The matter came to court, of course. Alan made his appearance in a bright blue, double-breasted gabardine suit left over from his theater days. He looked like someone from another century. The judge listened carefully to Alan’s story, then turned to the policeman. “Did you pull your gun on this gentleman?” “Yes.” “Did he hit you and take it away?” “Yes.” “Case dismissed.”

In the six years that Alan worked at Santa Cruz, however, what drew the most attention to him was the garden, in which so much grew with such abundance, and without the use of artificial fertilizers or pesticides. In that period of time, Alan introduced three basic techniques that have since had a strong influence on gardening throughout the United States. The first is the raised bed. A traditional approach, the raised bed (described in detail in chapter 10) is ideal for small-scale intensive gardening, especially using hand tools. Although it was practiced in some biodynamic circles and by Peter Chan (author of Intensive Gardening the Chinese Way) at the time, the raised bed was virtually unheard of before 1970 in this country.

Since its inception at Santa Cruz, detailed documentation of the increased productivity and decreased water and fertilizer requirements of raised beds, along with clear instructions on how to establish and maintain them, have been published by another early acquaintance of Chadwick’s, John Jeavons, in his book How to Grow More Vegetables. The raised-bed technique is now widely promoted in publications ranging from the Troy-Bilt Rototiller catalogue to the Peace Corps’ self-sufficient farming manual.

In my view, Alan’s second major contribution was his emphasis on the value of gardening with hand labor and hand tools. By treating gardening as an artistic physical discipline, he rekindled a sense of the joy and dignity of working outdoors. (He also, in part, inspired the founding of Smith & Hawken, now a leading supplier of fine hand tools for the garden.)

Alan’s third contribution was his emphasis on the mixed garden. In this he is not unique: backyard gardeners have always liked to grow a mixture of vegetables, herbs, flowers, and fruit. But Alan did it in a special way, one that mixed style and substance.

By 1972, Alan was again ready for something new. In that winter and the following spring, he helped establish two community gardens in California, in Saratoga and in Green Gulch, a Zen Buddhist retreat north of San Francisco. Then he went north, invited by Richard Wilson, a rancher in Mendocino County, to start a garden school in the remote California town of Covelo.

A few apprentices followed Alan to Covelo, bringing with them that same old Rambler, a horsehair mattress Paul Lee had given him, and little else. From what was there in the local leaf mold, barnyard manure, and soil, and from a few seed and plant orders, the project quickly took shape. Soon eight acres were under cultivation, and a growing number of apprentices, reaching forty or more at times, came to study and garden. The same techniques initiated at Santa Cruz—double-digging, hand watering, companion planting, and the emphasis on compost, herbs, and the old-fashioned standard seed varieties—were continued at Covelo. (Double-digging is described on pages 156-157, companion planting on pages 193-194 and 231.) Lorette pruning was introduced as well, and a large, circular herb garden with stone paths was built. An entry in the Covelo log book, reproduced here, shows how they planted Royal Sovereign strawberries.

Covelo logbook entry

From Covelo it is a two-hour drive to the highway and the next gas station. Movie theaters and other forms of entertainment are equally distant. What made new apprentices find their way to such a remote place and the put up with the rigors of hand cultivation once there? Growing awareness of the crisis in technological agriculture, and a concern for world hunger and for building a sustainable way to produce food were powerful motives. Equally, Alan’s charismatic reputation attracted many.

One of them, Fred Marshall, lived in Alan’s house for five years at Covelo and served as one of his two aides-de-camp. The day began at 3:30 A.M., when Alan arose to prepare for his morning lecture. Not infrequently, he awoke discouraged by the magnitude of the task before him, the challenge of rebuilding a link between man and nature that he felt had been lost.

Fred would typically begin with the morning ritual of grinding coffee beans. As he did, he would ask questions and report on farm activities, engaging Alan intuitively, discursively. One thing would lead to another, the birds would begin their predawn songs, and Alan spirits would begin to lift. Soon he would be busily looking up names in reference books, making a few notes, thinking out loud. By the time of his lecture, he would have once again transformed himself into a powerfully persuasive speaker, ready with his lines and his feelings.

The lecture might, for example, be about legumes. These plants are important because they build soil and the bacteria on their roots help “fix” nitrogen, making it available for plants. Alan maintained that these bacteria and the other biological life associated with legumes helped prevent fungus problems in the garden, and he liked to grow a variety of legumes and turn them under, into the beds, a process called “green manuring.” By recounting the appearance of a plant and its use in ancient Greece and Rome, as well as its traditional place in English farms and gardens, he was able to communicate a practical, complete picture of its role for his students.

Fava beans (Vicia fava) were one of his favorite green manures. This bean has been frown since prehistoric times, as we know from finding evidence of it in the archeological sites of the lake dwellers in Switzerland and at Glastonbury, in England, and was mentioned by Virgil. In ancient cultures, its scent was thought to cause mental disorders, and the white flowers, with their dark purple blotches, were symbolic of funerals. The fragrance is also reputed to be an aphrodisiac, and Alan enjoyed reporting that it was for this reason that friends he had known in Lincolnshire had kept their female servants on the premises when the fields of fava bean were in flower.

In the genus Vicia—the vetches—there are about 150 species. Vicia cracca, the tufted vetch, is a perennial with bright blue flowers that was traditionally grown in hedgerows. A closely related legume, Onobrychis viciafolia, is, like the vetches, a member of the subfamily Faboideae. The Greek word onos means “ass,” and brycho means “to consume greedily”—this plant is not only a soilbuilder but is also obviously excellent fodder. The French peasants who grew it extensively certainly were aware of this: their name for it, sainfoin, means “holy hay.”

If Covelo represents the zenith of Alan’s arc across the 1970’s, it also marks the beginning of his decline—here his health began to fail him. The cold winters aggravated his old back problems, making him irritable and harder to work with. New apprentices, who did not know him well, were less tolerant of his eruptions. More ominously, it was learned that he had prostate cancer.

It was clear he needed better weather and a different situation. Feeling a mixture of hope and dejection, almost as though exiled, Alan traveled south, settling for a short time in Sonoma, California, still looking for a place to build another garden and school. In a letter written February 1, 1978, to his friend Father Michael Culligan, he describes one brief prospect:

The dream: known as the spa of 1850, the Soda Springs. A superb facade of mountains, perfect soils, escalations. A veritable Cote d’Azur setting. Stream and waterfall, and all the buildings solid stone. The entire project in skeleton. Burned out in 1925, the timber all gone, stone almost all in perfect condition, sitting, waiting, for… What a prayer answered! Housing for all, hostel, clinique. And beyond all dreams, a colossal rotunda, used as a ballroom.

Also a large wooden house, unburdened, for immediate use. And the bubbling spa waters, like to Vichy. This is all beyond belief. Richard [Wilson] flew down and saw it. I feel he thinks it vastly too, too much.

We do not so regard it, and the Sonoma persons are vastly excited also. It is really all-the-year-round growing. What more perfect for the staff and students?

One building lends itself vitally to a chapel. We’re pursuing all out and to have a meeting with the new owner. Any terms are obvious to agree to. It must come off!…Our warmest greetings to you,

Chadwick.

The project did not come off. The property was not, in fact, for sale. Alan’s health and hopes worsened daily.

There was to be one more chimera. Hearing about a religious community in New Market, Virginia, that had just purchased 1,300 acres of land with the intention of making a garden on it, Alan wrote to them. Upon receiving an encouraging reply, he embarked on a last, desperate venture.

His friends at Covelo were more than helpful. They loaded a semi truck so full of plants and greenhouse glass the driver almost refused to take it. But the three-year-old black currants, the eighteen-inch-wide asparagus roots, and the four-year-old perennial flowers all made it from one coast to the other, and in the winter of 1978-1979 in the mild climate of the upper South, Alan planted what amounted to a ready-made garden. But the overnight magic was short-lived.

The following fall the New Market group fell delinquent in its payments on the land, and the project came to an abrupt halt. Alan’s cancer had by then become “impossibly painful,” as he wrote to a friend, and he needed a nurse. Death was approaching, and it looked as though he had no place to go.

A young woman at the New Market garden, Acacia Downs, then took on the job of caring for Alan. For a short time they lived in a house in Virginia, out of sight of the fields where the garden had been and where cattle now grazed. Freya visited, as did Richard Wilson. Quickly, places were located where Alan might pass his final hours, including the Findhorn Institute in Scotland and a monastery in the mountains near the Mojave Desert in California. But Alan chose, at the invitation of abbot Richard Baker, to return to Green Gulch.

From November 1979 until the middle of the following year, Alan and Acacia lived at the Wainwright [Wheelwright] Center at Green Gulch, in a cottage set in a grove of redwood and Monterey pine. Alan ate little and seldom went outside. Every day, flowers from the garden he had inspired were brought to his room. He and Acacia looked over his favorite art books. To feel that he was a part of the Green Gulch community, he gave lectures three or four times a week on various topics such as roses, garden technique, and his spiritual views.

Before he left Virginia, Alan had asked Acacia to give away or otherwise dispose of many of his things, including paintings, letters, clothes, etc., because he didn’t want people “chasing the name of Alan Chadwick.” In his last months, his underlying tenderness came to the fore. Not that his temper completely disappeared, however. One day, while reading to him, Acacia picked up a pear she had brought with her and casually took a bite out of it. Alan instantly rose up in his bed, raging at her. “You beast!” he shouted. “How can you insult the gift of food so?” And then in explanation, “A pear such as that should be held before your eyes. Its fragrance should be savored and its form admired before you bite into it, my dear. Don’t you know this pear is the culmination of centuries of man and nature cultivating each other? It is a gift and a precious delight. Do not spoil it with carelessness.”

Alan died on May 25, 1980. His funeral was as extraordinary as his life. Hundreds of people gathered at Green Gulch for it. Father Culligan wore his ceremonial robes, burned incense, and chanted the ritualistic Latin that Alan adored. Richard Baker conducted a Buddhist ceremony and erected a stone to commemorate Alan that looks out over the Pacific.

Father Culligan, who knew Alan’s old world of cathedral, hedgerow, and plays in small towns in rural Ireland, and who often walked along northern California beaches with him, remembers Alan this way:

That was the place to meet Alan Chadwick. Not in a room, but [with] the little birds running along the strand, the foam, the fog, the mist, and the Burberries up around our ears, there he’d talk about modern man.

Then he’d stop and gaze out, with that gaze he had. He’d look out with that craggy, rocky countenance, and gaze into the horizon with the seagulls squawking around us and the smell of the seaweed, into the timelessness of the sea.

Alan’s legacy, especially the use of raised beds and French intensive planting, has become so popular as to be almost routine today. The garden he started at Santa Cruz is still going strong; it now serves as the nucleus for an accredited Agroecology program (see the listing in appendix A), where research into alleopathy, or companion planting, is being carried out.

Return to the top of this page